Born in Watertown, Wisconsin, in 1900, Mary Woodard Lasker is widely credited as one of the driving forces behind the National Cancer Act. She came from humble roots, but over just a few decades, she emerged front and center with the elite of New York and Washington, DC.

“She was a mover and a shaker at a high level,” notes Howard Bailey, MD (PG ’91), director of the University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center and a professor of hematology, medical oncology and palliative care at the UW School of Medicine and Public Health. “She knew everybody, including presidents, and really pushed them to act on the causes she cared about. She’s really credited with pushing the idea of the NCI, the national cancer centers and the war on cancer.”

After creating and selling a successful Depression-era company, Lasker eventually turned her attention toward civic initiatives and causes. Along with her husband, she founded the Albert and Mary Lasker Foundation in 1942, with the intention of encouraging investments in medical research to tackle the major causes of death and disability, including cancer, in the United States at that time.

In that same period, she worked to transform the American Society for the Control of Cancer into the organization now known as the American Cancer Society and initiated its funding of cancer research in the early 1940s.

Throughout her life, Lasker received major honors and recognition for her work, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1969 and the Congressional Gold Medal in 1989. Her image also adorned a postage stamp in 2009.

Today, Lasker’s spirit and legacy carry on through her foundation, which presents awards each year to scientists for key advances in basic science and clinical medicine research. Many award winners have gone on to win Nobel Prizes, such as UW–Madison’s Howard Temin, PhD, professor, who won a Lasker Award in 1974 before winning the Nobel in 1975.

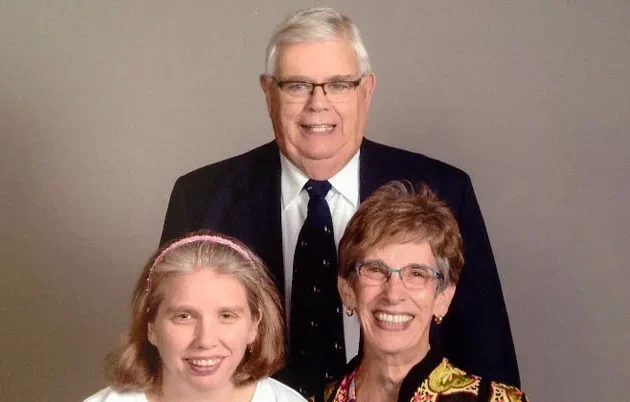

“She was really a woman of the times,” recalls Marshall Fordyce, MD, Lasker’s great-nephew and a Lasker Foundation board member. “Her focus on the funding of science and research was an incredibly important tool for enabling society to better understand things like cancer that really impacted the daily lives of citizens. Somehow she tapped into that in a very deep way.”

While Lasker didn’t live to see cancer completely eradicated, Fordyce says that if his great aunt were still alive, she’d be amazed by the progress toward that goal.

“I think she would be thrilled with the fruits of the investment in biomedical research in which she played such a key role,” he shares. “Just seeing the new biological medicines that have come forward that really didn’t mature until after her death. I mean, really curative therapies for some diseases. I actually think she’d be blown away by what science has been able to achieve.”