But even with decades of experience, the ambitious goal that President Nixon laid out in 1971 — to cure cancer — would not be easy.

Richard Burgess, PhD, SMPH emeritus professor of oncology, likens fighting cancer to standing next to a railroad track and being asked to stop an oncoming train with nothing but a wrench in your hand.

“There’s no way you’re stopping it,” he says. “You could throw that wrench at that train a million times and never even come close to stopping it. That’s the way our knowledge was back then.”

But Burgess notes that if you studied the diagrams and the inner workings of the train, you could potentially build a foundation of basic knowledge necessary to achieve the goal.

“You could recognize that there are certain vulnerable spots in the train where, if you stuck a wrench in where the gears are coming together, you could stop the train,” he describes. “And that’s exactly what’s happened over the last 50 years.”

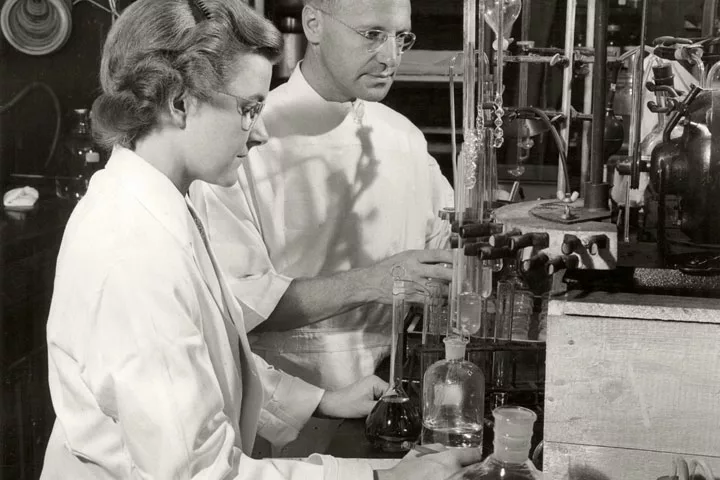

In 1971, Burgess had just arrived in Madison to work in the McArdle Laboratory. Funding from the National Cancer Act helped him establish his lab and dive into research. Having discovered the first positive transcription factor — a protein that effectively turns genes “on” — Burgess gradually built a research operation dedicated to understanding the ins and outs of the protein machinery of gene regulation, which helped researchers build their knowledge of what cancer is and how it operates.

As Burgess likes to say: “Today’s basic research produces tomorrow’s new treatments.”

Forward Momentum

Throughout the years, research advances made at UW–Madison have directly led to new, more effective treatments for cancer. That includes tamoxifen, which became one of the most widely utilized treatments for both preventing and treating breast cancer.

UW–Madison also is the home of TomoTherapy, a specialized form of radiation therapy that targets cancer cells and avoids healthy cells.

Today, that legacy of developing paradigm-shifting cancer therapies continues in new and exciting ways, from creating personalized vaccines made from a patient’s own cells to developing more targeted and effective immunotherapies that can be used as first-line treatments.

For instance, the Program for Advanced Cell Therapy was launched in 2016 to develop personalized cell technologies for improving health outcomes in children and adults with unmet medical needs, such as radiation-caused dry mouth, and testing those therapies through first-in-human clinical trials.

UW Carbone also has established itself as a leader in precision medicine; it is home to the Precision Medicine Molecular Tumor Board (PMMTB). Developed as a collaboration among UW Carbone and some of the state’s largest oncology practices, the board reviews cancer cases based on patients’ specific genetic mutations, and it recommends patient-specific targeted therapies.

Since its inception six years ago, the Tumor Board has reviewed more than 5,500 cases, with the annual number of cases increasing every year.

“We learn a lot from our patients, and it inspires us to try and understand what’s going on with individuals or groups of patients who have unusual cases,” shares PMMTB co-director Mark Burkard, MD, PhD, SMPH professor of medicine. “But at the end of the day, I think the biggest win is for the patients.”

Innovative Spirit

A lot has changed over the past 50 years. There are now more than 50 NCI-designated comprehensive cancer centers in the United States. Thanks to significant research advances made possible by the National Cancer Act of 1971, cancer is much more preventable and treatable. And more cancer patients survive today than ever before.

What hasn’t changed during all this time is UW Carbone’s spirit of innovation, a deep commitment to research and patient care, and a desire to make life better for individuals with cancer.

It’s what the UW Carbone Cancer Center’s namesake would have wanted because it’s what he preached. After all, he had a favorite phrase, one that the center still lives by today: “Cancer research has a face: the face of our patients.”