Recently, studies by Dave Fraser, UW-CTRI director of research administration, and colleagues from the Wisconsin Department of Health Services showed that financial incentives can powerfully motivate low-income smokers to engage in treatment and actually quit smoking. In addition, UW-CTRI scientists — including Megan Piper, PhD ’06, Danielle McCarthy, PhD ’06, Jessica Cook, PhD, and Tanya Schlam, PhD — have developed new treatments for smoking, using powerful new research methods.

The late U.S. Surgeon General C. Everett Koop, MD, once said quitting smoking was at least as difficult as quitting cocaine or heroin; subsequent research backed that assertion. UW-CTRI researchers have committed to answering the question, “What makes the hold of tobacco use so tenacious?”

“We know the same systems in the brain that are activated by nicotine are activated when an infant sees its mother,” explains Baker. “It is clear that nicotine has the potential to turn on very basic and powerful brain-reward and motivational systems.”

UW-CTRI investigators also have discovered that flavors seem related to tobacco use. For instance, Stevens Smith, PhD, and his colleagues have shown that smoking menthol cigarettes appears to reduce the likelihood of quitting smoking. And recently, Piper, the UW-CTRI associate director for research, and Doug Jorenby, PhD, its director of clinical services, have examined motives for smoking and vaping. These studies should help researchers better understand how addictive e-cigarettes can be, whether smokers are using them to quit, and the health effects of the devices.

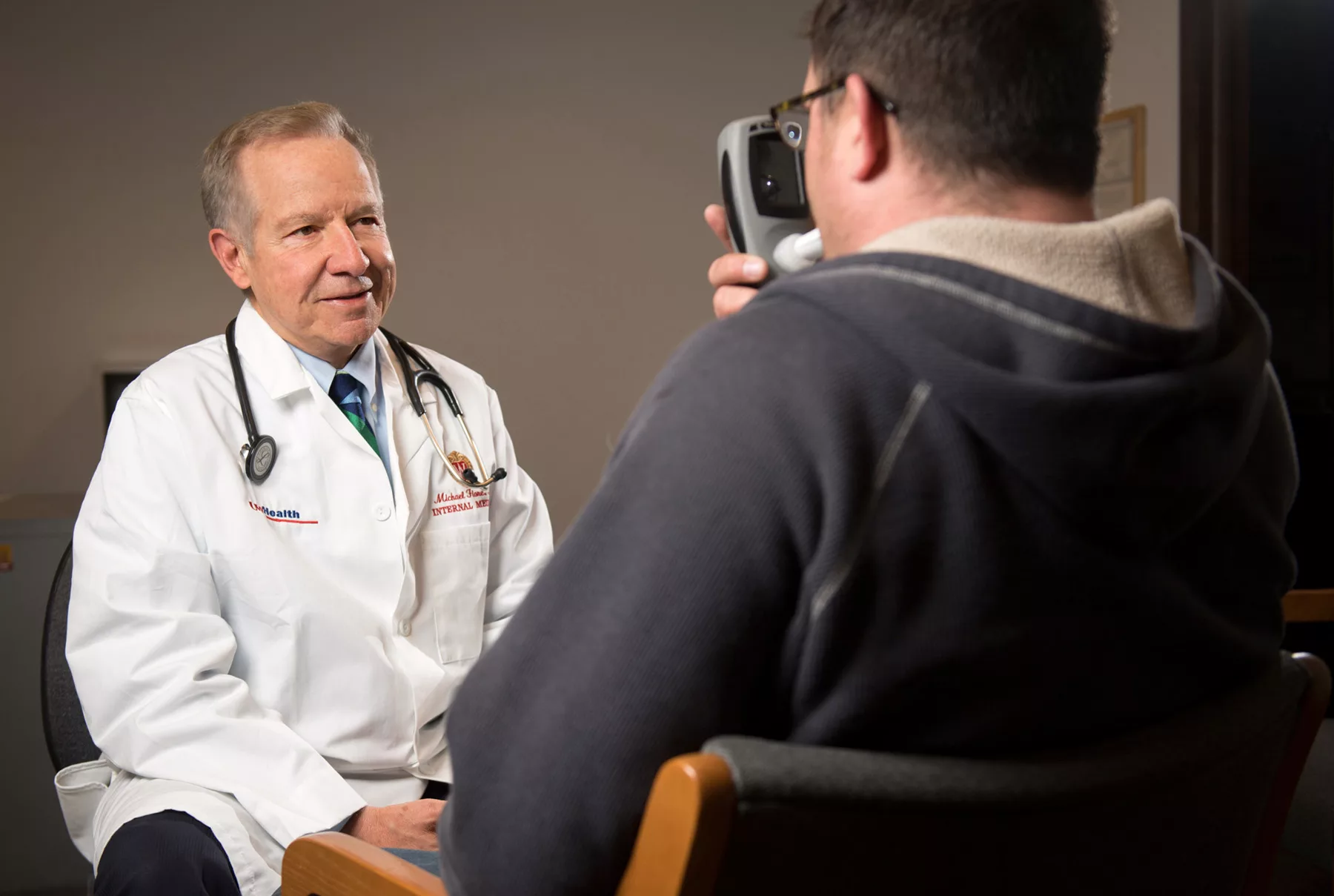

All-Points Bulletin to Health Care Providers

In 2008, the U.S. Public Health Service released its updated Clinical Practice Guideline, Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence, which was assembled by a large team of scientists from throughout the nation, led by UW-CTRI and chaired by Fiore. Like an “APB” to law enforcement officials, the guideline signals to clinicians that they need to be “on the look-out” for their patients’ tobacco use and:

- Ask about tobacco use at every visit

- Advise those who use tobacco to quit assess the patient’s readiness to quit (research shows 70 percent want to quit)

- Assist with quitting by providing medication and counseling — in-person or via referral to the Quit Line

- Arrange for follow-up

The former director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Tom Frieden, MD, MPH, heralded the guideline, saying, “What you have here is the best of the best in the release of a clinical practice guideline. In the process, content, practicality and the rigor of its work, I really salute all the people who worked on it, for what really should be a model for any clinic or medical practice.”

In the early 1990s, UW-CTRI researchers were the first to propose making tobacco use a vital sign — something doctors would assess at every visit, just like a patient’s blood pressure. When doctors intervene, smokers are twice as likely to quit. Back then, only one of five patients was asked by their doctors if they smoked. Now, nearly every patient is asked that question.

“This sort of systematic change in health care delivery is our goal,” says Rob Adsit, MEd, UW-CTRI outreach director.

UW-CTRI’s outreach team strives to embody the Wisconsin Idea by taking the latest research about how to help patients quit and sharing it with doctors, nurses, psychologists, pharmacists, dentists and other providers from all disciplines. They’ve worked with more than 22,000 professionals representing every health care system in Wisconsin. The team helps systems incorporate the latest research into their

standard of care.

Because clinicians are so busy, one of UW-CTRI’s aims has been to help doctors refer smokers to the Quit Line at 800‑QUIT‑NOW. It’s a win-win: patients get free, state-of-the-art treatments to quit smoking, while doctors can help more patients eliminate smoking from their lives.

Leveraging Technology

UW-CTRI has worked with Epic Systems Corporation — the Dane County-based worldwide leader in electronic health records (EHR) technology — to design and test a system that allows clinicians to electronically refer patients who use tobacco products to the Quit Line. The system provides service outcomes to clinicians in a secure, “closed‑loop” manner.

Several health care systems, including 37 UW Health clinics, have implemented the EHR-based referral program.

Putting Tobacco Away for Good

Fiore recently penned a commentary in the New England Journal of Medicine that included a blueprint for ending tobacco use in the United States. He outlined these strategies to put the proverbial handcuffs on this leading killer:

- Implement the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s full authority for tobacco product regulation

- Mandate the inclusion of graphic warning labels on all tobacco products

- Provide barrier-free access to proven tobacco treatments

- Raise state and federal cigarette excise taxes, with the rationale that the more tobacco costs, the less people use it

- Prohibit the sale of any tobacco product to people younger than 21

- Sustain successful national media campaigns

- Focus on helping populations with the highest smoking prevalence

- Enforce the Housing and Urban Development smoke-free housing rule

- Expand tobacco research

- Fully fund comprehensive, statewide tobacco-control programs at CDC-recommended levels

- Extend comprehensive, smoke-free indoor-air protections to all Americans