Fundus Focused on Art and Science of Eye’s Inner Landscape

As Ansel Adams once said, “We must remember that a photograph can hold just as much as we put into it, and no one has ever approached the full possibilities of the medium.”

The world-renowned landscape photographer likely never imagined an image as rich and scientifically meaningful as today’s ability to photograph the intricate details of the “landscapes” of the inner eye, or retina. This helps experts better detect and understand blinding diseases, with the goal of finding ways to prevent and treat them.

Continually leveraging the capabilities of this medium, the University of Wisconsin Fundus Photograph Reading Center (FPRC) specializes in reviewing super-high-resolution photos of the retina for clinical trials related to diabetic retinopathy, diabetic macular edema, macular degeneration, retinal vein occlusion, uveitis, inherited retinal diseases and drug safety trials. These trials range from single-site studies to large, international, multi-center projects conducted at a few hundred clinical sites.

The FPRC partners with the National Institutes of Health (NIH), academic medical centers and private corporations, such as pharmaceutical manufacturers.

“We collaborate with about 1,800 sites around the world. It’s exciting that clinical researchers in this many places are familiar with what we can accomplish at UW–Madison,” notes Amitha Domalpally, MD, the center’s research director. The FPRC is among a few such reading centers of this type in the world. Its history stretches back to 1969, the year before Matthew Dinsdale “Dinny” Davis, MD (PG ’55), helped elevate the UW School of Medicine and Public Health’s ophthalmology service — then part of the Eye, Ear, Nose and Throat Division of the Department of Surgery — into the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences (DOVS).

Longevity Leads to Success

A physician-scientist, Davis became the first DOVS chair, founded the FPRC and worked closely with research collaborators to develop a systematic approach to diabetic retinopathy. Davis was a leader in developing both the protocol for taking stereoscopic retinal photographs and the methods for reproducibly analyzing the retinal features of diabetic retinopathy.

Barbara Blodi, MD, FPRC medical director and DOVS professor, says a number of staff have worked at the center for more than 20 years. Such longevity holds true for its ongoing collaboration with the National Eye Institute (NEI), part of the NIH, to conduct clinical trials and create disease-specific severity scales that help predict prognoses.

For instance, the chief of the NEI’s Clinical Trials Branch, Emily Chew, MD, joined that institute near the conclusion of the landmark Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study led by Davis and for which the FPRC served as the reading center.

“The UW Fundus Photograph Reading Center was already a well-known entity under the direction of Dr. Davis, who collaborated in the development of the classification of diabetic retinopathy that has been used for decades in clinical research,” recalls Chew, who also is the director of the NEI’s Division of Epidemiology and Clinical Applications. “This was a major achievement. Dr. Davis also collaborated with the NEI by chairing one of the first clinical trials, the Diabetic Retinopathy Study, which established the gold standard for treatment of diabetic retinopathy. That standard also holds today.”

An ophthalmologist who specializes in medical retina, Chew notes that these accomplishments were made possible by the FPRC’s work to train many investigators and photographers in the field — a role that remains central to the center’s mission.

Domalpally and Blodi, among others, have frequent contact with Chew through several grants the FPRC currently holds with the NIH.

“Together, we have carried out multiple clinical trials that have impacted how we care for patients,” says Chew. “The FPRC’s collaborative spirit and intellectual input have been key to this success, and staff at all levels display a high level of professionalism.”

Domalpally describes a typical scenario for the center’s work with sponsors: “When a pharmaceutical company is developing a new drug and gets beyond successful animal trials, it needs to do Phase I, II and III clinical trials in humans. Clinical trial leaders call upon us to help determine which imaging tests would be most appropriate, and later to read images and analyze results.”

Center Highly Regarded for Its Credibility

Studies at the FPRC are double-masked, so the highly trained readers do not know which research subjects are getting specific treatments versus placebo. Readers do not look at images like a clinician would; instead they track clinical features over time and send that information to statisticians, who view unmasked data at the end of the trial.

Blodi and Domalpally — along with Michael M. Altaweel, MD (PG ’00), professor, and Mihai Mititelu, MD, MPH, assistant professor, both of DOVS — serve as principal investigators for imaging studies at the center. The FPRC routinely involves medical students and residents through faculty-initiated research projects. Trainees benefit from the large database and imaging know-how of the personnel, as well as their data analysis rigor and biostatistics expertise.

“Because our center is completely neutral and independent, and we are an academic institution, our credibility is excellent,” Blodi shares, recalling that the FPRC’s and Davis’ reputations were among the reasons she chose to join UW Health and DOVS, where she provides patient care and conducts research, respectively.

“As a retina specialist, I am most involved with macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy and retinal vein occlusion in both clinical and research realms,” says Blodi, a co-principal investigator for the NIH-funded, five-year Study of Comparative Treatments for Retinal Vein Occlusion 2 (SCORE2) clinical trial of monthly eye injections for the treatment of retinal vein occlusion in 362 participants.

Published in May 2017 in the Journal of the American Medical Association, the multi-center SCORE2 study is a head-to-head comparison of Avastin (bevacizumab) vs. Eylea (aflibercept), two widely used drugs in the treatment of retinal vein occlusion. At six months, the drugs were equally effective in improving vision, with an average improvement from 20/100 to 20/40. SCORE2 also provided valuable cost-effectiveness information, as Avastin is a much less expensive drug.

Before starting work on a clinical trial, FPRC research photographers train and certify photographers and clinicians at collaborating sites worldwide. Training covers new software and imaging systems, among other things. Each clinical site that conducts studies through the FPRC must have the capability to acquire high-quality images.

Additionally, strict criteria for large, multi-center trials require all physicians in the trial to gather routinely for meetings, which could be anywhere in the world. An FPRC representative spends a couple of days at each of these meetings to train and quiz physicians and other study personnel in the imaging requirements of the particular trial. Beyond that, most work is done via cloud-based transmission of images and data.

“Our center participates in up to 35 trials at any given time, so that’s a lot of people to train and certify,” says Domalpally. “Our partnership is important because when photographers can take good photographs, the studies have reliable data.”

She describes one technique — optical coherence tomography (OCT) — which has been available for clinical use for about two decades. Researchers have constantly improved it to the point where they can see to the level of 3 microns deep in the retina of the living eye, almost like a histopathological section. Photos show the retina’s thickness, as well as areas of thinning and swelling, or other pathologic changes.

“Retinal OCT scans look like a piece of multi-layer cake for which photographers, researchers and clinicians can see the icing and all of the layers of the retina in great detail,” Domalpally describes.

The technique has become the most common form of imaging because it is noninvasive and is easier both on the patient and the photographer.

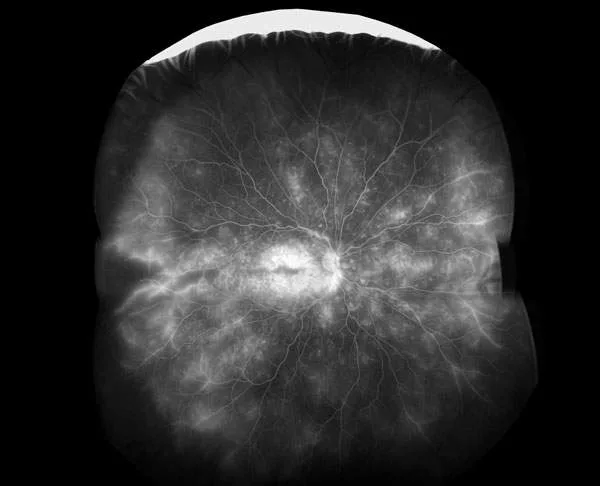

More involved techniques, including ultra-wide imaging, require the skills of highly trained photographers and specialized equipment. In some procedures, such as fluorescein angiography, a dye is injected into the patient’s bloodstream, and ophthalmic photographers use filters to capture images of the dye as it moves throughout vessels of the retina to detect areas of damage.

“As we interpret each image, our goal is to identify changes from the normal structure and compare it to refined grading protocols and disease classifications,” she explains.

Our work is not yet done.

– Barbara Blodi, MD

Technology evolves rapidly, and the FPRC team eagerly greets the challenge while keeping one foot in the past — such as maintaining its old slide transparencies in a secure archive for historical reference.

“Researchers always want the latest and greatest, but they need to have comparable standards. For instance, to make sure a new drug compares to an old drug, which may have been analyzed using former techniques, we can call upon new and old analysis systems,” says Domalpally. “I feel our center can compare ‘apples to apples’ in this way.”

Of course, staying current is the name of the game, Blodi shares.

“I admire our image readers because they are cross-trained for any type of study. Efficiency is important, as there’s a big demand for our services,” she says.

While the FPRC has made major contributions to ophthalmic clinical trials and produced landmark changes in the treatment of all-too-common diseases, Blodi notes, “Our work is not yet done. Many patients worldwide are still suffering vision loss from retinal diseases and other eye conditions that have no treatment.”

To that end, she collaborates on a number of pilot projects with basic scientists in DOVS and with scientists who are part of the McPherson Eye Research Institute to help find new treatments.

Blodi believes one of the FPRC’s major contributions relates to the way ophthalmologists think about eye conditions.

“Clinicians are excellent observers and learn from their experiences. They want to integrate results of effective clinical trials into their practice,” she says. “When the FPRC’s work leads to development of a severity scale, such as for diabetic retinopathy or macular degeneration, physicians have the ability to tell patients not only about treatment options but what to expect in terms of prognosis, which is incredibly valuable.”

With that in mind, the FPRC faculty and staff plan to continue the momentum of the center’s first five decades, as they aim to fulfill Davis’ vision: fostering retinal research and supporting clinical investigators around the world.