The Center for Rare Diseases provides comprehensive medical genetics, multispecialty services and state-of-the-art diagnostics and clinical trials for a broad spectrum of patients in Wisconsin and the rest of the United States who are living with rare diseases. In November 2021, it was designated by the National Organization for Rare Disorders as one of 31 Centers of Excellence in the nation.

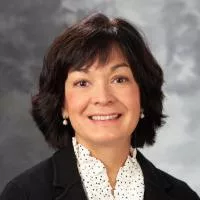

“We are excited to join the Center of Excellence network, and with the National Organization for Rare Disorders, we are committed to providing comprehensive, patient-centered care,” Keppler-Noreuil notes. “This is an exciting step to advance medical breakthroughs, improve care planning, and support patients, families and physicians.”

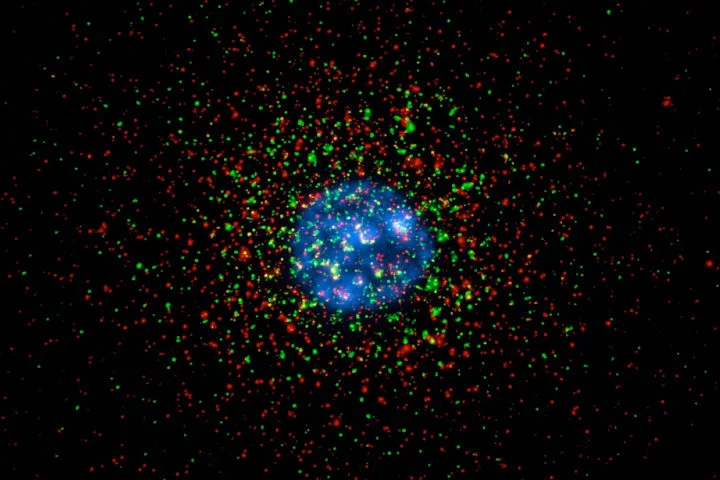

The Center for Human Genomics and Precision Medicine has been increasing capacity through an expanded research facility and new investigators. In February 2020, the center and its laboratories moved into its new space of more than 9,000 square feet in a new section of the Wisconsin Institutes for Medical Research building. Soon, an additional 9,000 square feet will be added to University Hospital to support clinical research, clinical genomics and diagnostics. The center also has helped departments recruit 15 faculty members whose research programs are devoted to areas such as genome pathology and development of new diagnostic tests.

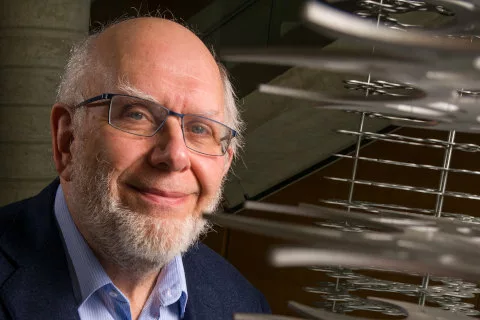

“This has been an exciting time with new faculty members developing programs, such as our Precision Medicine Research Service and planning our first Precision Medicine Symposium in 2022,” says Jacalyn McHugh, assistant director, Center for Human Genomics and Precision Medicine.