Change in WMAA’s Corporate Status

Many alumni may not realize that WMAA was created in 1956 as a non-stock corporation. Over the past 64 years, the landscape has changed significantly.

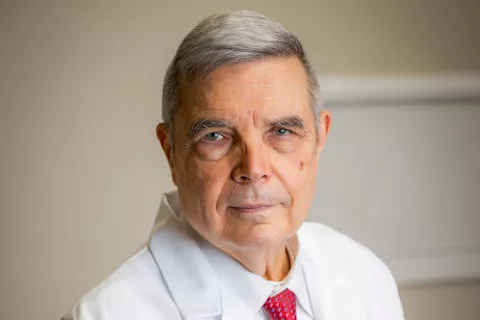

When colleagues describe Dennis G. Maki, MD ’67, they use superlatives. Extraordinary. Unsurpassed. Legendary.

Over the course of his 46-year career on the faculty of the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health’s Department of Medicine — 28 of which were spent as chief of its Division of Infectious Disease — Maki has reached generations of learners, influenced legions of peers, and most importantly, saved the lives of countless patients worldwide.

As a physician, Maki is known for his insatiable thirst for knowledge, superhuman memory and tireless work ethic. But the self-described “farm kid” from northern Wisconsin also is deeply generous — he’s a Bascom Hill Society member who has made substantial philanthropic contributions to the School of Medicine and Public Health and across the UW–Madison campus.

For those reasons and more, Maki was named a recipient of the Wisconsin Alumni Association’s highest honor, its Distinguished Alumni Award, which he received from UW–Madison Chancellor Rebecca Blank in October 2019.

The valedictorian of his high school class in Edgar, Wisconsin, Maki dreamed of playing college basketball. But Maki’s father was adamant that he attend UW–Madison, so the General Motors Scholar and honor student earned his way through his undergraduate education there by working 15 to 18 hours each week in the dining hall.

At UW–Madison, during his sophomore year, “over the scrape table, emptying dishes,” Maki met Gail Dawson, a physical therapy student from Neenah, Wisconsin. They dated until 1962, when they got married the same week they earned UW–Madison bachelor’s degrees: physics for him and physical therapy for her.

Maki went on to earn a medical degree in 1967 from the UW Medical School (now the SMPH), taking a year off in the middle to conduct research and earn a master’s degree in physics from UW–Madison.

Recalling thoughts during his freshman year, he says, “I had acquired a deep attachment to UW–Madison and its extraordinary academic excellence that made me determine that somehow, some day, I would join the faculty of this great university.”

In 1967, the Makis and their young daughter, Kim, moved to Boston, where Maki began an internal medicine residency on the Harvard Medical Unit of Boston City Hospital. “I was on call every other day and was sometimes at the hospital continuously for 10 days at a time,” he shares.

Living in Boston on a resident’s salary was challenging. Maki remembers hoping his car would hold up because they couldn’t afford to replace it. He also reflects on how his wife used a stroller to get groceries and take their children to doctors’ appointments.

“But we had a wonderful time during those years,” he says. “We recognized right from the get-go that this was an extraordinary opportunity — that I was getting a training that you could not buy.”

Two years into his residency, he was drafted into service at the Epidemic Intelligence Service of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Serving as the acting chief of a national study on hospital-acquired infections sparked a deep, lifelong fascination with infectious disease, laid the foundations of his future career and earned him a commendation medal from the CDC.

In 1971, the Maki family, which then included second daughter, Sarah, and son, Dan, returned to Boston for Maki to complete a senior and chief residency and a year of infectious disease fellowship at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Meanwhile, three senior faculty members in the UW Department of Medicine — Robert F. Schilling, MD ’43 (PG ’48), the head of hematology and oncology and former department chair, and Richard E. Rieselbach, MD, the head of nephrology, who are now emeritus professors, and Calvin Kunin, MD, the first head of infectious disease — knew Maki was about to finish his training. They invited him to visit UW–Madison to consider joining the faculty.

Despite having three job offers at Harvard, in 1974, Maki returned to his medical school alma mater as an assistant professor in its Department of Medicine, as well as chief of the Section of Infectious Diseases and hospital epidemiologist at UW Hospital and Clinics (now UW Health). In 1975, he received the endowed Ovid O. Meyer Professorship in Medicine.

The move was good for Maki’s growing family and for his emerging career.

“When they invited me back here, I saw an immense opportunity,” he affirms. “There was very little in infectious disease practice or research here, and the nascent field of hospital-acquired infection control was crying for good research. The best decision I ever made was to return.”

Over the next four decades, Maki’s exemplary clinical skills in both infectious disease and critical care elevated his reputation in the eyes of colleagues across the state, nation and world.

“Physicians throughout our region refer their patients to UW Hospital so Dr. Maki will have an opportunity to diagnose and treat their patients’ life-threatening illnesses,” notes David Andes, MD (PG ’95, ’99), the William A. Craig Endowed Professor of Medicine and chief of the Department of Medicine’s Division of Infectious Disease.

Having devoted his research career to the prevention of hospital-acquired infections, Maki has published more than 370 papers that provide much of the scientific foundation for infection prevention practices in hospitals worldwide.

“He is widely considered one of the fathers of modern-day hospital-acquired infection prevention,” confirms Andes.

Maki also has conducted research on the clinical application of novel agents for the treatment of septic shock and the treatment of antibiotic-resistant infections.

Further, his prolific outreach activities are considered by many to be unsurpassed by other School of Medicine and Public Health faculty members. He has visited virtually every hospital in Wisconsin — and held visiting professorships or given invited presentations in 49 of the 50 U.S. states and more than 75 medical schools.

Maki’s expertise is reflected through consulting roles at the CDC, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and United Kingdom’s National Health Service. He also has received lifetime achievement awards from the Association for Professionals in Infection Control, Society for Health Care Epidemiology and Infectious Diseases Society of America.

Maki has influenced the careers of countless medical students, internal medicine residents and infectious disease fellows. He is a top-ranked educator who has been selected as the Investiture Marshal by seven graduating SMPH classes, and he has received more than a dozen teaching awards from the Department of Medicine, the SMPH and UW–Madison.

“Dr. Maki is what we refer to as a ‘triple threat’ — a physician who is exceptional at patient care, research and education,” reflects School of Medicine and Public Health Dean Robert N. Golden, MD. “He has set the gold standard in each of those areas, and in doing so, has created the type of synergy across these missions that represents the very best traditions of academic medicine.”

In 2001, Maki received the School of Medicine and Public Health’s Folkert Belzer Lifetime Achievement Award for outstanding contributions in academic medicine, and the UW–Madison Hilldale Award for Distinguished Contributions in Teaching, Research and Service. In 2009, he received the Wisconsin Medical Alumni Association’s Distinguished Alumni Award.

While accepting the Wisconsin Alumni Association Distinguished Alumni Award, Maki reflected on a day at the end of his first undergraduate year at UW–Madison, when he realized that someday, he wanted to be a member of the faculty.

“Over the past 46 years, I’ve lived my undergraduate dream,” he told the audience. “The wonderful people I’ve had the chance to work with — the students, fellows, residents and patients — have all made me a better physician, better scientist and better person.”

Today, Maki is still working: he sees patients, teaches and pores over scientific literature.

“After a half-century of practicing medicine, Dr. Maki still participates in weekly Grand Rounds presentations, absorbing the latest data and raising insightful questions regarding its interpretation and applicability,” shares Golden.

From their home in Madison, Maki and his wife stay in close contact with their three children — Kim, a linguist and mother in Seattle; Sarah, a nurse and mother in Phoenix; and Dan, a radiologist and father, also in Phoenix — and their partners, as well as the six children in the next generation.

They also grow organic apples, berries and vegetables on a small farm in Richland County that they bought 12 years ago. “Whenever I get a couple of days off, we go out to ‘the farm,’” he shares. “I am returning to my rural Wisconsin roots.”

“I have told young people — who I have recruited over 40 years — is that the University of Wisconsin is a great place to spend a career,” he continues. “It has an extraordinary collegiality. While highly competitive, it wants young faculty to thrive and succeed.”

As a true Badger, Maki has dedicated his career to helping others thrive and succeed — whether they’re learners, researchers, colleagues or patients. For him, that’s what it means to be in academic medicine.

He reflects, “Academic medicine is a very unique calling and endeavor. Our focus is not [just] on what we are doing now. We are always looking down the road to the future and [thinking about] what we can do better.”