Christian Capitini Describes Immunotherapy Successes

For nearly 10 years, Capitini has maintained an active research lab at the UW Carbone Cancer Center while also providing care for children with cancer at the American Family Children’s Hospital.

Twenty-five years ago, James Thomson, VMD, PhD, became the first in the world to successfully isolate and culture primate embryonic stem cells. He accomplished this breakthrough at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, first with nonhuman primates at the Wisconsin National Primate Research Center using rhesus monkey cells and marmoset cells. And just a few years later, he published a world-changing breakthrough on human embryonic stem cell derivation.

When Thomson — now a professor in the Department of Cell and Regenerative Biology at the UW School of Medicine and Public Health (SMPH); director of regenerative biology at the Morgridge Institute for Research; and professor of molecular, cellular and developmental biology at University of California, Santa Barbara — came to UW–Madison in 1991 for his veterinary pathology residency, he shared with colleagues that two important factors influenced his move.

First, UW–Madison has the Primate Research Center, supported by the National Institutes of Health, and he had just completed his postdoctoral training in embryology at the Oregon Regional Primate Research Center. Second, as he already had his eye on stem cell biology and its potential in science and medicine, he was attracted to the renowned Division of Transplantation in the UW School of Medicine and Public Health’s Department of Surgery and UW Hospital and Clinics (now UW Health).

Born in Illinois and interested in biology at a young age, Thomson’s studies took him to the University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign to study biophysics and then to the University of Pennsylvania to pursue his veterinary medicine and molecular biology doctorates. There, he became interested in embryonic stem cell research, studying mouse embryos and mouse stem cells. However, as he often shares in his talks, the mouse embryo is organized far differently than the human embryo. A better model was needed if scientists were going to unlock the developmental and functional secrets of these cells to better understand human biology.

Fortunately, when Thomson was hired as the head veterinary pathologist at the Primate Research Center in 1995, he was given the freedom to explore monkey embryo derivation when time allowed. UW–Madison was already famous as a center of embryology and in-vitro fertilization (IVF) research, mainly through the College of Agricultural and Life Sciences (CALS). Also, in 1984, the world’s first IVF rhesus monkey, “Petri,” had been born at the Primate Research Center through research led by Barry Bavister, PhD. Even though the world’s first human born through IVF, Louise Brown, had come into the world seven years earlier in England, little was known about the technique overall and how to improve its success, which was not much higher than natural fertilization at the time.

Thomson’s work at the Primate Research Center with scientific colleagues and technical experts in reproductive biology led to his first successful isolation and culture of rhesus monkey embryonic stem cells in 1995. This required only one preimplantation embryo, flushed non-invasively from a rhesus monkey uterus. He then repeated the feat with common marmoset stem cells a year later. Thomson published these breakthroughs in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and Biology of Reproduction, respectively.

Next, he acquired unused frozen embryos donated with patient consent through the IVF Clinic at UW Hospital. He acquired a private lab and private funding through Geron Corporation. Using the same culture techniques he honed with the monkey embryos, within two years he had grown the world’s first successful human embryonic stem cell lines.

Thomson published his findings in Science on November 6, 1998. A news media and political whirlwind ensued. Thomson even relocated to University Communications in Bascom Hall for several days, working with research communications director Terry Devitt to accomplish interview after interview with science and mainstream reporters from around the world. Patients hoping for miracle cures, religious leaders, politicians and bioethicists all weighed in on embryonic stem cell research. Among the latter was R. Alta Charo, JD, professor of law and bioethics at UW–Madison, who has served on numerous expert advisory boards of organizations with an interest in stem cell research. Debates focused not only on whether to allow federal funding for embryonic stem cell research, but whether the research should continue at all.

Thomson quickly reached out to SMPH faculty collaborators who had interests spanning the breadth of human diseases. They included Timothy Kamp, MD, PhD, professor, Department of Medicine (heart disease); B. Lynn Allen-Hoffmann, PhD, professor, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine (skin regeneration); Su-Chun Zhang, MD, PhD ’91, professor, Departments of Neuroscience and Neurology (spinal cord injury and motor neuron loss); and Jon Odorico, MD (PG ’96), Department of Surgery (diabetes).

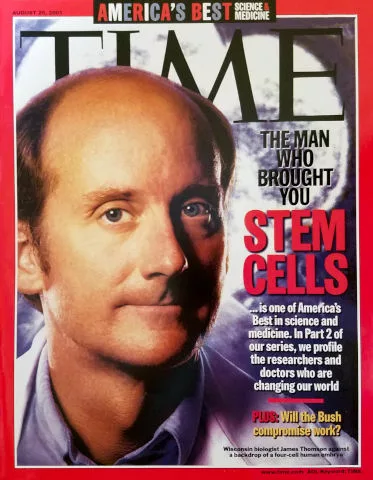

Meanwhile, Thomson continued working in his lab and establishing more collaborations. In August 2001, President George W. Bush allowed limited federal funding for stem cell research, which allowed Thomson to continue working with the cell lines he already had derived and share them with colleagues, many at the SMPH. In 2008, President Barack Obama expanded federal funding for embryonic stem cell research involving IVF clinic patient-donated embryos. Madison also was home to the first National Stem Cell Bank and the nonprofit WiCell Research Institute, which continues to advance stem cell technology through research, education and technical support for the scientific community.

As the need for centralized support for stem cell research, collaboration, student education and public outreach grew, the SMPH and the UW Graduate School together founded the UW–Madison Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine Center (SCRMC) in 2007.

The center’s first co-directors were Kamp, who had grown cardiomyocytes from Thomson’s hES cells in 2003, and Clive Svendsen, PhD, a former professor in the SMPH Departments of Anatomy and Neurology, who was interested in growing motor neurons from stem cells to study amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. William Murphy, PhD, a professor in the SMPH Department of Orthopedics and Rehabilitation and the College of Engineering’s (COE) Department of Biomedical Engineering, served as a co-director from 2012 to 2018. Kamp remains the director, and Randolph Ashton, PhD, an associate professor in the COE Department of Biomedical Engineering, is the associate director.

An SCRMC faculty executive committee, initially led by Thomson, continues to guide the center. Its charter members included SMPH faculty members Odorico and Linda Hogle, PhD, professor, Department of Medical History and Bioethics. Additional faculty members from the SMPH, COE, CALS and WiCell have rounded out the team that has advised the center over the years. In addition to the Primate Research Center and the SCRMC, other campus units have been instrumental in supporting UW–Madison scientists and advancing the field of stem cell research. They include the Waisman Center, Morgridge Institute for Research, Wisconsin Institute for Discovery and Biotechnology Center.

Spurred by the SMPH’s history of pioneering discoveries in stem cell research and the enormous potential for exciting, medically relevant advancements, the school created the Department of Cell and Regenerative Biology in July 2011.

Over the past two decades, stem cell research at UW–Madison has grown from involving a handful of scientists to nearly 100 from more than 30 schools, colleges and departments. Today, the SCRMC continues to grow through its support from the SMPH, the Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research and Graduate Education, and philanthropic donations. The center supports research, academic education, weekly seminars and public outreach. It also co-hosts the annual Wisconsin Stem Cell Symposium, now in its 15th year.

Thomson predicted that, just as monkeys were important for early stem cell derivations and basic science research, the field would circle back to them for the large animal transplant studies needed before human clinical trials could take place. Studies underway at the Primate Research Center include those in the Preclinical Parkinson’s Research Program led by Marina Emborg, MD, PhD, professor, SMPH Department of Medical Physics, and stem cell-based therapies to prevent immune rejection in solid organ transplants when anti-rejection medicines are eliminated, led by Dixon Kaufman, MD, PhD, professor, SMPH Department of Surgery. Research by Igor Slukvin, MD, PhD, professor, SMPH Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, and Ted Golos, PhD, professor, UW School of Veterinary Medicine, is aimed at exploring genetically edited immune cells grown from stem cells to prevent HIV infection, and developing immunotherapies to treat AIDS.

Peiman Hematti, MD — a professor in the SMPH Departments of Medicine, Pediatrics and Surgery — worked with Kaufman to establish his preclinical studies at the Primate Research Center, among just a few places in the nation capable of performing the type of transplantations required. Expert research technicians, veterinarians and animal care staff supported the research, which is now in human clinical trials.

As the director of UW Health’s Clinical Cell Processing Laboratory, Hematti has been involved with most of the clinical cell therapy trials at UW–Madison, including two trials with Kaufman; several heart disease-related trials led by Amish Raval, MD, associate professor, SMPH Department of Medicine; and several CAR T-cell therapy trials, including one to treat leukemia with Christian Capitini, MD, associate professor, SMPH Department of Pediatrics. Other clinical trials around the world involve stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes grown by Kamp and retinal pigment epithelial cells grown by David Gamm, MD, PhD (PG ’02, ’03), professor, SMPH Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, and director, McPherson Eye Research Institute. Further, Jacques Galipeau, MD, the SMPH’s inaugural associate dean for therapeutics development and a professor in its Department of Medicine, leads the Program for Advanced Cell Therapy.

Ever since monkey and human embryonic stem cells emerged from Thomson’s lab, newer discoveries — such as the derivation and culture of human induced pluripotent stem cells, epigenetics and CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing — have furthered the promise of regenerative medicine. Many preclinical and clinical trials now involve these technologies.

The main uses of stem cells today include research to understand the human body, discover the genetic origins of disease, grow new cells and tissues for transplantation, and grow cells and tissues for testing pharmaceuticals in the laboratory before animal and human trials commence. Stem cell research is helping animals, too. For instance, pets get cancer, diabetes, arthritis and other diseases that stem cell therapies may be able to treat.

Researchers and government agencies uphold high standards and strict criteria for advancing patient therapies that are based on well-designed, thorough clinical trials. The SCRMC maintains a public resources page on its web site that offers guidance and facts for patients considering stem cell treatments.

Meanwhile, scientists and students around the world continue to use Thomson’s original five human embryonic stem cell lines as the gold standard for studying stem cell biology. Thomson has always maintained that the greatest legacy of pluripotent stem cell research will be its use as a powerful tool to understand the human body. This research has so much to reveal about how cells develop, function, differentiate, communicate, age and die. The field is advancing in ways most people could not have imagined two and a half decades ago.