Molly Carnes Breaks Through Biases

Carnes hadn’t formally studied gender issues, but early on in her career she was keenly aware how few women held leadership or research positions in academic medicine, and that led to a new course.

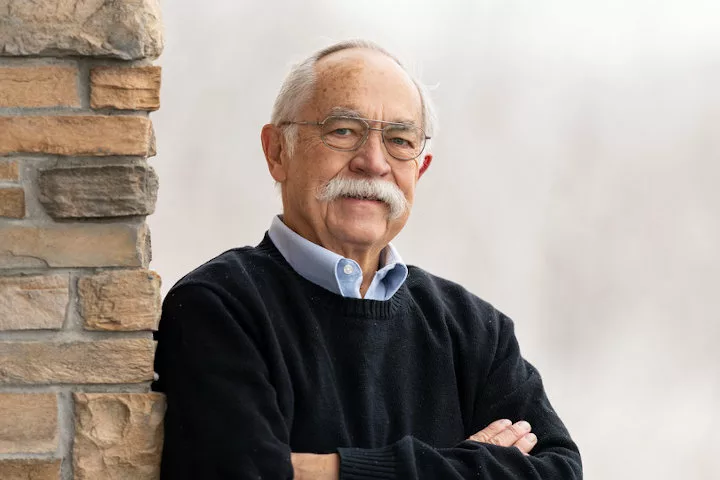

The years that Paul A. Wertsch, MD ’70, spent at University of Wisconsin–Madison — first as an undergraduate and, later, as a medical student at the UW School of Medicine and Public Health (SMPH) — left an indelible mark on his career.

For one, as a young man living in Madison in the mid- to late-1960s, Wertsch says he couldn’t help but be influenced by the political unrest and social activism he saw all around him. For another, it’s where he met his classmate and future wife, Kay Heggestad, MD ’70 (PG ’75). As the first woman to graduate from the SMPH’s Family Medicine Residency Program, Heggestad shared Wertsch’s pioneering spirit. Together, they devoted their careers to realizing the progressive and reformist ideals that punctuated their early years on campus. Some related memories are recorded in Heggestad’s self-penned 2017 obituary, which went viral for its humor and tell-it-like-it- is account of navigating the health care system as a patient with multiple myeloma.

Certainly, their greatest manifestation of these ideals is the independently owned Wildwood Family Clinic, which Wertsch, Heggestad and Daniel J. Barry, MD (PG ’76), founded in 1978 on Madison’s east side.

Recalling the “egalitarian spirit” that inspired their choice to found a clinic, Wertsch says, “Working in a group where you’re not in control just wasn’t appealing.”

From the onset, the trio focused on “getting the right people in and being a small group so we didn’t have to go through a huge corporate process to get things approved,” says Wertsch, adding that the ability to adopt new practices allowed them a different kind of relationship with patients.

“We believed if you told people the truth, you could get them to work with you,” he notes.

Illustrating the formula’s success, Wildwood has grown to include a dozen physicians — including some who earned their medical degrees at the SMPH, others who graduated from the school’s Family Medicine Residency Program, and one who holds a master of public health degree from the SMPH. They also employ several physician assistants and physical therapists, as well as psychiatric social workers.

Having recently opened a second location in Cottage Grove, Wisconsin, the clinics emphasize treating the whole patient by offering in-house laboratories, physical therapy rooms, imaging, massage therapy and health coaching.

“We were holistic before people were holistic,” Wertsch shares.

Another ground-breaking aspect of Wildwood Clinic is that, from the beginning, the founders made a point of hiring women physicians. Wertsch notes that Heggestad was the second female doctor to deliver babies in Madison, with the first being the physician who delivered her.

Further, having always emphasized maternal health, Wildwood is among the few clinics in Madison that provide lactation consultants outside of the hospital and is the city’s only Milk Collection Depot for nursing mothers who wish to donate their milk.

Although Wertsch left his practice when his wife was ill and “just didn’t go back,” he is far from retired; he jokes, “I still go to meetings and bother people with my ideas.”

He also remains passionately involved in reforming the health care system. He has tackled the health care worker shortage, supported gay rights and spoken out against a faltering Medicare system.

Recalling back to 2003, when Wertsch was serving as president of the Wisconsin Medical Society, he says, “It already looked like there would be a shortage of nurses.”

Indeed, that shortage continues, and Wisconsin also is facing additional health provider shortages, including primary care physicians, surgeons and child psychiatrists.

Wertsch’s work through the years on several task forces and work groups has given him a handle on the reasons behind these shortages. For instance, he notes, less competitive salaries and difficult schedules can deter future physicians from practicing in primary care. Wertsch aims to help the public understand what’s at stake — such as how a shortage of generalists will lead patients to visit more costly specialists, who may order unnecessary, costly tests, he says.

Through a study conducted by the Wisconsin Council on Medical Education and Workforce, Wertsch hopes “to get some facts and find a way for society to help solve these issues.” Given his record, there’s reason to believe he will succeed.

Bolstering the next generation of physicians has always been important to Wildwood Family Clinic’s health care providers. Thus, they mentor SMPH medical students at the clinic and teach SMPH family medicine residents at St. Mary’s Hospital.

“Teaching keeps us sharper and ensures that we will have good doctors to care for us in the future,” says Wertsch.

A longtime active member of the Madison chapter of Parents, Families and Friends of Lesbians and Gays, Wertsch brought this advocacy to the national level when, in 2005, he was named the inaugural chair of the American Medical Association’s (AMA) Advisory Committee on Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender (GLBT) Issues. He successfully led that committee as it developed a resolution convincing the AMA to reject the Don’t Ask Don’t Tell policy, which was in effect in the U.S. Military from 1994 to 2011. The resolution argued that the policy forced physicians to lie in military personnel records, which were open to commanding officers, or risk their patients’ careers.

Noting that the AMA’s stance was quite a turn for an association characteristically reticent to take political positions, Wertsch says, “We got them to stand by it, and there was a lot of national attention on this. Eventually, the military rescinded this policy, and it influenced the country at large.”

He found similar success as an advocate for gay marriage. As chair of the Wisconsin Medical Society’s Task Force on GLBT Issues, Wertsch convinced the organization to support gay marriage, arguing that dependent children of GLBT parents should receive the same benefits, including health care and parental sick leave, as those with heterosexual parents. Later Wertsch succeeded in this cause with the AMA. As medical societies began to publicly recognize the ways in which gay rights impacted their professions, the public also gained awareness and acceptance.

About Wildwood’s 2012 announcement that it would be the first clinic in the region to consider turning away new patients insured by Medicare, Wertsch recalls, “I was afraid of how patients would react. But they were quite positive after they understood how Medicare reimbursement affects the physician office.”

Noting that it was not an easy choice, Wertsch reflects on his own aging patient population as he says, “After all, as a family doctor, your practice kind of grows with you.”

Yet, as someone who proudly served for eight years on the AMA Council for Medical Service, Wertsch understood very well the frustrating circumstances of the system. He hoped that by taking a stand, the Wildwood Clinic’s leaders might help the public understand the situation, too.

Agreeing to be profiled by journalists, Wertsch explained how the government was reimbursing primary care visits at a fraction of the cost compared to specialty visits. Not only was this an unsustainable business model for the clinic, he argued, it ignored the role that primary care providers can have in drastically reducing health care costs. After all, whether treating strep throat, diagnosing early symptoms of appendicitis or delivering healthy babies, primary care often translates into preventive care.

Even for more complex diseases such as Type 2 diabetes, he says, patient education and counseling are essential.

“But people don’t want to change their diets. They want to take pills,” Wertsch notes, adding that this leads to a situation in which insurance companies continue to reimburse visits to specialists, and researchers keep developing drugs “that allow people to keep eating what they want.”

About that time, he says, “I think a lot of people learned much more about the economics of how this works.”

And while he feels that his messages still face an uphill battle, his commitment to medical care that encourages patient education, partnerships and advocacy remains unthreatened.

“I feel privileged that I could take part in people’s lives,” Wertsch says of the deep relationships he built with his patients. “And they took part in mine. It was a two-way street, and it was wonderful.”

Noting that specialists may enjoy higher salaries and better schedules compared to primary care physicians, he shrugs and says, “But I don’t think specialists enjoy their lives as much — and they probably don’t get hugged by their patients as frequently as I have, either.”

Paul Wertsch, MD ’70, remembers the progressive origins of Madison’s Blue Bus Clinic, the city’s first free clinic that started out educating and counseling community members about sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and psychotropic drug use.

“When I came to medical school, the American Medical Student Association was sort of a staid organization, but the Student Health Organization (SHO) was just being developed. I went to Austria for an international medical student meeting, and that really influenced me as far as my activism was concerned.”

Upon returning to Madison in 1968, Wertsch served as president of the SHO until he earned his medical degree in 1970.

“We were an independent student organization, but for advice and help, we would talk to Dr. Ted Goodfriend,” he says.

“In Wautoma, Wisconsin, there was a migrant worker clinic, and we got funding to work there in the summer of 1968. Student volunteers and faculty members from UW–Madison went there once a week to staff the clinic outside the pickle farms. Over time, we wanted a bus to get to the migrant camps,” he recalls.

Wertsch, along with fellow medical students — including Kay Heggestad, MD ’70 (PG ’75), Neal Halsey, MD ’71, and Christine Nelson, MD ’70 — convinced Dean Eichman to purchase an old school bus.

Wertsch recalls that, once again, Goodfriend’s support proved helpful because he let the students use a toll-free phone in his lab to purchase the bus. With a coat of donated blue paint, the Blue Bus began its long and storied existence.

At the end of the 1968 growing season, students found themselves with nowhere to use the bus, so they parked it on Mifflin Street. There, it became an impromptu free clinic in which medical student volunteers provided information and counseling about STDs and psychotropic drugs to the Madison community.

“The first patient was a dog that had overdosed on someone’s marijuana brownies,” recalls Wertsch.

Thus began a model that continued long after the literal bus rolled to a stop. In 1970, the Blue Bus Clinic moved out of the vehicle and into the basement of a building on North Bassett Street, where it served the community for decades. It is now part of the University Health Services.